Welcome back to this journey through The Kolbrin.

So, we are currently working our way through The Sacred Registers; and this post will, like the previous five, deal with more of the relatively short chapters (this time, Chapters 15-18) that we find in this section of The Book of Scrolls (aka The Book of Books, The Lesser Book of the Sons of Fire, and The Third Book of the Bronzebook).

Well, let’s kick this post off with Chapter 15. It purports to be ‘A Scroll Fragment’ so it’s anyone’s guess what the wider context is, but what we are given is a kind of formulaic question and short answer session of the type that is found in many esoteric – including masonic – rituals; indeed The Kolbrin states that it is all that remains from sixteen damaged pages ‘relating to an initiation ceremony’ that were salvaged from The Great Book of the Sons of Fire.

There are 18 stanzas in total, all of which demand that the candidate for initiation assert that it is they themselves who must take responsibility for their actions on their path through life. The actual questions and short answers are as follows (with a running commentary from yours truly):

Who will reward or punish me? I will. In other words, we must be the impartial judge of our own actions and reward or chastise ourselves accordingly.

Who besets my path with sorrow? I do. We are responsible for own misfortunes and should not blame others for our own shortcomings and mistakes.

Who can grant me a life of everlasting glory? I can. It is down to us alone to lead a good and righteous life (which, according to The Kolbrin, is the recipe to move on to the next plane of existence as one of the goodies).

Who must save me from the horror of malformation? I must. Again, it is we as individuals who must bear personal responsibility for our thoughts and deeds, so that evil and wrongdoing do not disfigure us into one of the ugly creatures that are made to account for their misdeeds at the time of reckoning (or, indeed, while still alive).

Who will guide my footsteps through life? I will. Do not rely on others to give your life direction. That energy and intent must come from within.

Who brings joy into my life and gladdens my heart? I will. Do not sink into despondency. Let your actions and demeanour be always positive and joyful, so that it is you – and not others – who affects your spirit.

Who brings peace and contentment to my spirit? I do. Inner tranquillity and blessed stillness come through our own efforts. Avoid annoying people, don’t get drawn into inflammatory situations, seek the peace within.

Who lightens the burden of my labours? None but myself. There’s a lot in this one, including what Lucius Annaeus Seneca wrote about it being easier to be led willingly than dragged along unwillingly, but in the spirit of this Kolbrin chapter let’s just say that, at some level, we all have a choice about what we take on and how we deal with that choice is up to us.

Whose courage will protect me from the workers of evil? My courage. We must muster our own courage to fight for what is right and just, and not hide behind, or rely upon others to do it for us. Find your courage! Often, it is only we, as individuals, who can stand firm and put ourselves in the path of a wrongdoer who is bullying their way into our or others’ lives.

Whose wisdom will guide me and enlighten my heart? My wisdom. The knowledge that feeds true wisdom does not grow on trees, it must be learned and earned. Our entire lives must be a learning process, and that is something that it is up to us to find time and space for. Learn well from your life-experiences.

Whose will rules my destiny? My will. A philosophical biggie, this one, but the short answer is that we are responsible for our own destinies. We decide what we want to become. We set our own goals and are, therefore, solely responsible for formulating a plan to strive towards them and generating sufficient energy to make it all happen.

Whose duty is it to attend to my wants? My duty. In other words, get off your backside and tend to your own needs. You are your own responsibility, so don’t rely on or expect others to do it for you. Contrary to what you may think, you are not the centre of the universe; so, no matter what your station in life, stop depending on other people and learn to depend upon yourself.

Who is responsible for my future state of being? I alone am responsible. Whether this question relates to the shifting circumstances of life on Earth or life after death, the answer is the same. The key is in the word ‘responsible’. Even when we feel we have been forced into doing something that affects our state of being (whether materially, emotionally or whatever) we are still responsible for allowing ourselves to be put under that pressure. So, this question’s all about having the Rationality to objectively analyse what’s about to affect you and finding the steadfastness to hold true and do what is right.

Who shields me from temptation? No one. Absolutely spot on, this one. The ultimate decision about whether to cave in to temptation rests with the individual. So, don’t have the gall to blame anyone else for your own weak will because the buck stops with you.

Who shields me from sorrow and suffering? No one. Bit harsh, the answer to this question, but it’s dead right. We can find comfort in the condolences and love of others, but sorrow and suffering are emotions that must be borne by each and every one of us alone. The Stoics would have us fortify our Rationality to the extent that we become impervious to inner pain, but that is easier said than done. In truth, we are all going to get hit from time to time by the curve balls that life throws at us, and coping with it is one of the harshest lessons we must learn – but learn it we must if we are to move on.

Who shields me from pain and affliction? No one. This is a bit like the last one, but it’s not quite as absolute in my book. If the pain and affliction come from disease, then yes, we do have to undergo the experience on our own; but if they come from attack or violence, then you may get lucky and be saved by a ‘guardian angel’. I guess, though, that this question is couched under the assumption that the initiate will seek to become self-sufficient where it concerns their physical protection and mental well-being and take steps to either acquire the skills to defend themselves or, just as good, learn to spot and avoid potentially threatening situations and/or vexatious people.

Who benefits from my toil and tribulation, my sorrow and suffering? Myself, if wise. This one’s easy. Acquire the wisdom to learn from your mistakes and setbacks in life, and make yourself a bigger, better person.

Who benefits from my temptations and afflictions, my sacrifices and austerities? Myself, if wise. A bit like the last one, this question and answer are about having the self-honesty to admit to past misdemeanours (temptations) and analyse mishaps (afflictions) as a step towards acquiring wisdom. Sacrifices and austerity, though, can be two-edged swords depending on the reason they were brought into play. If the intent behind them was for self-improvement, then did they achieve the required result? If the intent behind them was for some selfish end, then that is not wisdom.

And that’s all there is in Chapter 15. What I’ve written above is far longer than the actual chapter itself, but I couldn’t help myself but bung in some self-help stuff.

Chapter 16 is just as short as its predecessor but the focus shifts to how an individual can have a better understanding of and, through that, relation with God as The Kolbrin’s religion sees that entity/power/concept (call it what best floats your own boat). It is entitled The Third of the Egyptian Scrolls (A Fragment) so here we have confirmation that what the scribe is describing is based on a peculiarly Egyptian take on man’s place in the multiverse.

It starts with the age-old concept of awareness not only of self (‘Know Thyself!) but of the world around us and the understanding of the duality (or reflection in each other) of all things – the as-above-so-below principle – a solid grasp of which is required if we are to come to terms with what we truly are and why we are really here on this Earth. To understand the heavens, we must first understand the Earth, and to understand God, we must first understand ourselves; but in order to achieve any of this, we must start from a position of ignorance, because, as the scribe points out, a man cannot know (in the sense of fully comprehend) love unless he has been loveless. This is a Great Truth, not just about love, but about anything really; it’s the old you must forget everything you thought you once knew in order to acquire true knowledge and wisdom on a blank sheet, as it were, with no prior misconceptions to cloud the teaching – the old ‘only when I can admit I know nothing can I begin to truly learn’ syndrome.

The scribe goes on to say that although this God is beyond the reach of normal human senses and intellect to discern and comprehend, Its (I’ll use the neuter pronoun for convenience sake) presence and purpose are there to be felt by those who make the effort.

The fragments of the chapter start to jump about at this juncture, as the next axiom reminds us that the point of life is to conquer adversity. Man must struggle against the current, not drift with the flow, writes the scribe. Furthermore, the onus to improve on the innocent babe-like state into which we are born is on us as individuals. The goal of earthly existence is not to further glorify God (because, as the scribe points out, this cannot be done), but to glorify man. Self-improvement is the name of the game here.

Empty rituals that attempt to worship God are pointless. A human’s time is better spent doing good for its fellow kind. The hand that offers practical help, says the scribe, is worth ten ‘wagging tongues’.

We must become steadfast and courageous in order to fight for what is good for ourselves and others. Struggle or perish, says The Kolbrin, because there is work to complete during our sojourn here on Earth. So, stop all the posturing and wind bagging and knuckle down to make it all happen.

The chapter ends with a portentous statement on the Meaning of Life: Man lives in God and God lives in man. This answers all questions. Well, not really, not all questions, but I suppose we could say that, just as every strand of DNA in an acorn carries the blueprint for the mighty oak, so every strand of DNA in us humans carries a blueprint of the multiverse itself. Yes? No? Maybe?

Chapter 17, The Sixth of the Egyptian Scrolls, carries on in like manner, so we won’t spend too much time on it. God permeates everything and is eternal, which is proof of everlasting life (in some form or other – the dissipation of the sub-atomic energy that was ‘you’ dispersed into the wider universal community as other things, perhaps?), God is omnipotent and beyond the ken of normal humans, God’s creative thought (=energy wave) brought everything into existence etc. etc. there is nothing here we haven’t heard before, but then the passage moves onto the foolhardiness of mankind where it concerns the folly of ‘humanising’ a concept whose reality is totally beyond its ability to get a mental hold on.

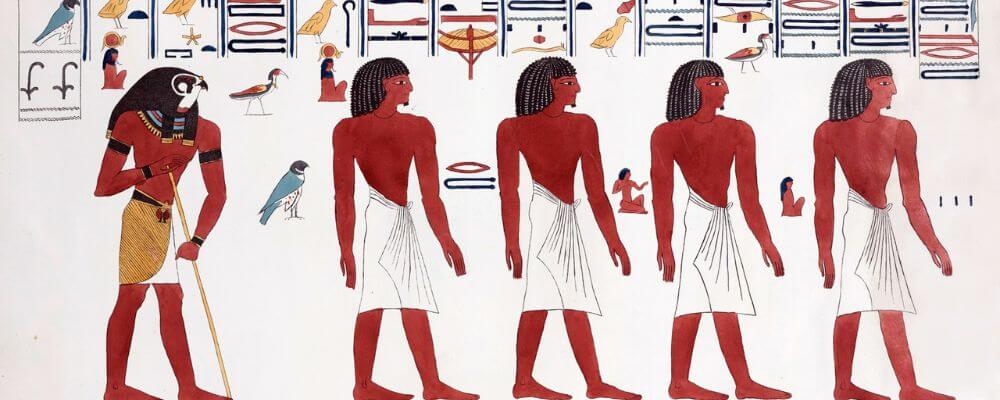

It makes no difference to God, says The Kolbrin, that humanity somehow anthropomorphises the deity by creating images in wood or stone of different facets of its own conception of God (or Gods) because God is above all that jiggery-pokery and mumbo-jumbo. By diminishing or diluting the true Godhead through attempts at corralling It into objects and vacuous prayers and rituals in efforts to make the whole thing more accessible to humans, mankind, writes the scribe, is doing itself a massive disservice because – and this is an important bit – Amongst earthly things man shall find nothing greater than himself. Now, you can take that last bit any way you want, but, for me, it rang a couple of bells. Not only does it tie in with the view expressed in the ancient Hermetica about humanity being a step down from the angels (gods-in-waiting in other words), but it seems also to be a kind of call-to-arms, an exhortation to look within and unlock the potential with which we are all born and become true children of the multiverse, with all the benefits and wonder that entails.

The last few paragraphs of Chapter 17 sort of repeat what it has already said: Humans worship God for selfish ends and have got it wrong when they imagine God as a kind of Super Human, the ultimate version of what mankind can achieve, because It is far greater than anything that we meagre creatures can conceive of. Mankind is in the thoughts of God although those thoughts are hidden from us, and God, being a part of us (as we are of It) accompanies us through the veil that separates life from death. God is us and all the planets and all the stars and all the galaxies and all the universes. All things, says The Kolbrin, begin and end with God.

The closing line of Chapter 17 enjoins us to realise that: This alone is wisdom, understand and live forever.

I’ll have more to say on how what might sound like religious claptrap could contain seeds of greater truths and aid us in some personal self-help at the end of this chapter, but, for now, let’s move on to Chapter 18.

Chapter 18 is entitled A Scroll Fragment – Two and, although it is not a natural sequitur to Chapter 15 – A Scroll Fragment One – which we encountered at the beginning of this post, it does purport to have something to do with initiation, citing as it does from what it calls The Book of Initiation and Rites. In its way, this chapter is very interesting as, although couched in religious terms, it does touch upon some really important concepts which, although they may seem a bit obvious at first, become quite mind-blowing when you begin to consider what they might imply.

It starts off with some standard God-created-and-sustains-all-things statements and reminds us of all the beauty with which we are surrounded: serene landscapes under shifting light, the smell of flowers, the delight of music and so on. And then the passage gets a bit deeper . . .

So, this God made available everything that humankind would need for a comfortable existence: daylight and wind, food and water, heat and coolness, the materials to build dwellings and make clothes – everything laid out so that man could improve his skillset and improve his knowledge (and this, of course, all ties in with The Kolbrin’s mantra about the Earth being a testing ground, which makes the whole thing sound a bit like a fantasy game with quest tools scattered around to use if you can work out how to). But the next comment – To all useful things guideposts have been planted along the way – is very curious because it seems to touch on the rather strange concept of the Doctrine of Signatures, an ancient teaching that asserted, amongst other things, that plants bearing a resemblance to certain body parts or symptoms of illness could be effective as treatments for them. The theory dates back to at least Greek or Roman times, but, if The Kolbrin is a tome containing genuinely ancient material and not some New Age rehash of established texts, this passage would suggest that the concept was around well before then.

And then it gets stranger still, because the scribe goes on – still quoting, we recall, from the Book of Initiation and Rites – and commences to lay out the logic behind why the universe has order and provides ‘proofs’ that the only viable explanation is that it was created by some kind of ‘Architect’ that he refers to as ‘God’. This is all, of course, veering into the realms of Freemasonry, whose rituals, it would appear, were founded on the texts of the ancient Greek Hermetica which were, in turn, developed from original Egyptian texts supposedly constituting part of the now lost (or perhaps legendary) magical Book of Thoth.

This excerpt from the Book of Initiation and Rites points to the obvious ‘order’ that is visible all around us (although you could argue that the ‘order’ we see in the world around us only appears so because it is ‘normal’ to we inhabitants of this Earth). When barley seeds are sown, says the scribe, man knows that what will sprout from the ground will be barley plants and not a random triffid or some such. Fire, he goes on, is of a single nature, always hot and never cold, so man can expect it to cook his food. Night follows day and the hours of light and darkness follow a fixed pattern as the year progresses. Oil is used to light lamps and water is for drinking – man knows never to confuse the two. Everywhere man looks there is order and the scribe concludes that man understands where there is order, there must be an organiser. If it were not so, he says, mankind would be a plaything of chance, buffeted by the winds of chaos.

Having satisfactorily supplied, in his own mind, ‘proof’ that everything on, in, or above this Earth is the product of some sort of divine Architect, the author of this section of the Book of Initiation and Rites tells us what that understanding brings out in him. He will acknowledge the order of the turning seasons by recognising what he owes his God with days of feasting and fasting. He will sing songs of praise, sung with a full heart and a mind conscious of why the praise is being offered – he will never just mumble along without thinking about the true meaning behind the words of his paean.

There is more of the same for the next couple of passages, along with a reminder that God is in everything, and Its majesty and purpose is beyond the ability of mere humans to grasp.

Chapter 18 ends with a warning that, although God created man in his own image so that mankind has the capacity to absorb and return God’s love, freewill was also given as part of the package and mankind has not used that part of the gift at all well. OK, I guess the question there is, what is the point of all this freewill stuff? It can’t be as vacuous as all that old ‘if you love something set it free, if it returns it is yours, if it doesn’t it never was’ tosh, because if this God-Architect is so omnipotent and beyond the intellectual grasp of humanity, why would it bother? Something as powerful as that would surely not dally in vanity. No, the answer must lie in the consideration that the God gets something out of the exchange. But what? If you’ve been following the Gurdjieff thread of this website, you’ll find a theory that might explain it. There, it is suggested that this ‘Great Architect’ actually needs humanity (and everything else in its ‘creation’ for that matter’) to function, in effect, as energy refiners and convertors, and freewill is an essential element in that operation because it is the catalyst that starts the process of energy conversion that will upcycle raw (or degraded) energy into something refined enough to keep the whole God-Architect show on the road. Why does this need to happen? Because – hold on to your hats – this God-Architect, while hugely powerful, is not immortal! Gasp! Shock! Horror! This God-Architect (or whatever else you want to call It), is, just like everything else, subject to entropy, and to counter that, It has conceived of a massively simple, yet elegant, ‘machine’ (of which we humans are a part) to continually reprocess degraded energy into useable fuel. In short, the Multiverse is one massive recycling plant powered by the principle of perpetual motion. There, how about that then? Put that in your pipes and smoke it! The Greenies would love this concept!

Right, enough of the grandstanding (or pathetic attempt to get you to have a read of some other sections of this website) and onto some self-help aspects of the chapters covered in this post.

The question-answer initiation rite of Chapter 15 was too good an opportunity to pass up for adding some self-help observations, so that’s what I did there.

I did, however, want to take another look at Chapter 17 and attempt to prise open the lid of the religious veneer to see what self-help titbits we can glean from what lurks underneath.

I guess the major takeaway from that chapter is that we must learn to honour and value ourselves. Whether or not you subscribe to the opinion that we are essentially little godlets-in-waiting, the consideration remains that there is nobody as important in our own lives as ourselves. By all means, worship the deity of your choice, but do not rely on It to sort out your life for you – only you can do that. There is, admittedly, comfort and energy to be generated and accrued from ‘communing’ with the object of your worship, but never lose sight of the understanding that you, yourself, are the originating catalyst for that energy. You did it, no-one else. Once you understand that is how the relationship works, you can turn the focus inwards and take control of generating that comfort and power without relying on any outside props. We all have the power to help ourselves and harnessing it begins with a little self-belief.

OK, that’s enough for now. The next few chapters (19-24) are so-called hymns from The Book of Songs and they are all pretty samey, so my next post will be a relatively short one, but I nevertheless hope to see you all there. Until then . . .