Welcome back to the Book of Gleanings, being a part of The Kolbrin. In the last chapter, we learned more about this enigmatic yet compelling character named Yosira – some kind of spiritual cum temporal ruler – who had taken it upon himself to educate and civilise the communities with which he came into contact, using a potent blend of common sense and good old-fashioned supernatural scaremongering. This latest chapter, entitled The Way of Yosira, gives us a deeper insight into the man’s take on the human soul, but before we begin it, I’m going to try to place the series of passages on his life (if, indeed, the ‘gleanings’ we are reading are genuine translations of original writings or traditions and not some modern rehashing of more recognisable myths and legends) within some sort of historical and geographical framework.

Now, I’ve already hazarded the guess that we may be dealing, chronologically, here, with a period roughly equivalent to pre-dynastic Egypt – a proto-Egypt, if you like. Admittedly, the management of land cultivation in a terrain dominated by a great river (which is reported as one of Yosira’s civilising achievements) could refer to any of the so-called great original civilisations, all of which grew up in great river valleys, but the very Egyptian ‘tone’ of the spiritual teaching that goes hand-in-hand with the education in practical affairs (such as personal hygiene and food production) leads me to lean towards Egypt. And then there is the man’s name, Yosira. Is it me, or does that sound a little too like the Egyptian Osiris? And by Osiris, I am not referring to the myths and legends of that name as a god, but as he was originally depicted in ancient stories; that is, as a civiliser and temporal ruler. On pages 362-382 of James George Frazer’s magnificent work The Golden Bough (the abridged version published in 1929) Osiris is attributed with all the civilising achievements that he is in the last few chapters of The Kolbrin (including that of introducing booze to the locals). The author of The Golden Bough (which is a masterpiece of comparative religion) is now long dead, but his work is still worth a read – if you have a spare decade or so (it’s quite dense for the most part).

Anyway, for my money, the character on whom The Kolbrin is reporting in these passages as Yosira is none other than that great historical civiliser of pre-dynastic Egypt, Osiris himself. OK, let’s move on . . .

The current chapter opens with Yosira attempting to educate his ‘people’ about the existence of the human soul. As usual, being eminently practical and understanding that such a potentially complicated concept needs to be dumbed down a bit to get the message across, he couches it in terms that are immediately accessible to his relatively primitive audience.

Inside every human, he says, there is a kind of passenger, a ’little man’ who is the Lord of the Body. This little man is not tied to the physical body but can depart whenever it needs to; in fact it does so whenever the body is asleep, and the departure becomes permanent at the point of death. Although invisible to most, the little man can be seen by the ‘Twice Born’ (whom we know from previous chapters to be those initiated into the higher arcana or truths). At death, the little man exits via the mouth, hangs around for a bit while it grows a pair of wings, and then flies off to the ‘Western Kingdom’ where the wings are shed and the little man can live without the need for a physical shell.

And Yosira wouldn’t be Yosira if he didn’t, at this point, chuck in a bit of practical advice disguised as supernatural mumbo jumbo. He understood that his audience would assume – because the Lord of the Body had departed and the shell was now just an empty container – that they could ignore the derelict corpse and leave it lying around, vulnerable to putrefaction and disease. So Yosira tells his people that unless the corpse is ‘purified’ by filling it with the esoteric hokew we heard about in the last chapter, it would attract, and become the abode of, ‘shades from the Place of Darkness’. Not very nice at all!

Probably realising he is onto a good analogy with this Lord of the Body thing, Yosira then goes on to dish out more practical advice of the sort we might dispense about sleep-walking and other psychological issues. Always wake a sleeper gently, he says, in case the Lord of Body can’t get back from its walkabouts quickly enough and the person becomes confused. In a similar vein, when psychosomatic problems or even madness occur (of the type that are not caused by the evil lukim that Yosira is otherwise fond of evoking as a reason for sickness) then they are likely due to the Lord of the Body falling asleep during the day, and people skilled in recalling it to wakefulness are employed (‘charmers’ the scribe calls them, although, in reality, they sound more like primitive psychotherapists).

Yosira didn’t stop at psychiatric solutions; he also taught medicinal botany (herb lore) and what sounds like the surgical procedure of cauterization. All these remedies, it seems, were written down in a tome entitled The Book of Medications.

The nature of the chapter switches abruptly at this point, and becomes another narrative telling the tale of Yosira’s civilising of yet more tribes and peoples. This time he sets his sights on the people of a place called Tamuera who, if we recall from the previous chapter, were singled out as being so beyond redemption that Yosira was willing to allow them to be slaughtered by ‘remote’ weapons of war (such as arrows and spears), the very missiles he had forbidden other tribes under his influence to use against one another.

According to The Kolbrin Tamuera was, at that time, a lawless place, full of ignorant, warlike savages spread amongst many different tribes who fought constantly amongst themselves. There was no monarchy, just the arbitrary authority of old men, and individuals called Charmers or Keepers of Customs or Tellers of Tales who held the people in thrall with deceits and delusions. So, not a very nice place then – at least not by Yosira’s high standards – and the scribe goes on to tell an intriguing little tale about just what charlatans this bunch of primitive con-artists – these Charmers and Keepers of Customs and Tellers of Tales – were.

One particular tribe of Tamuerans – the Children of Panheta (the name of their god) – lived on stilt-built reed huts in swamps located in the middle of dense forests. Not too far distant, but away from the water and the trees, lived another tribe who dwelt in caves and holes in the ground. This lot were nameless and worshipped the Dark Spirits and something called the Kamawan of the forest which carried men off at night. When those who had been seized by the Kamawan returned to their own people, they had been struck dumb and soon died of a madness, clawing at their own bodies.

Well, that’s all very supernatural and woo-woo, you may be thinking; but no, the whole thing was a massive con perpetrated by the so-called Charmers. It was they who were kidnapping the forest people during the night and carrying them off to a secret place where they would pin back their victims’ tongues with thin thorns. The tongues would swell up and the power of speech was lost. The Charmers would then pierce their victims around the waist with very thin slivers of wood that could not be found or removed and, their pièce de résistance, they drove thin wooden splinters into the bridge between the private parts and the anus (ouch!) that could never be discovered by anybody attempting to help the poor, agonised wretches.

Yosira, quite understandably, and as he should, brought down a mighty curse on any Charmer who practised this abomination, and all those he cursed died in madness, suffering a painful death from ‘a demon which ate away their bellies’. Good on ya, Yosira, way to go; although, knowing what we do by now about Yosira’s very practical modus operandi, I strongly suspect that this ‘demon’ he brought down on the Charmers was very likely a poisonous potion of his own concoction. That would be very much in keeping with his normal practice of blending superstitious awe with a very down-to-earth solution to achieve a practical end. Anyway, whatever he did, it worked, and the so-called Kamawan were never again heard of in the land.

The next passages are all about Yosira bringing the skills of civilisation to the land. It would appear that he taught men basic metallurgy (which, if we are talking about copper, the first ‘worked’ metal, could place this passage as far back as 4,500 – 3,500 BC – if The Kolbrin is to be taken as a genuine chronicle that is), pottery, the art of weaving, and last, but by no means least, the art of brewing beer.

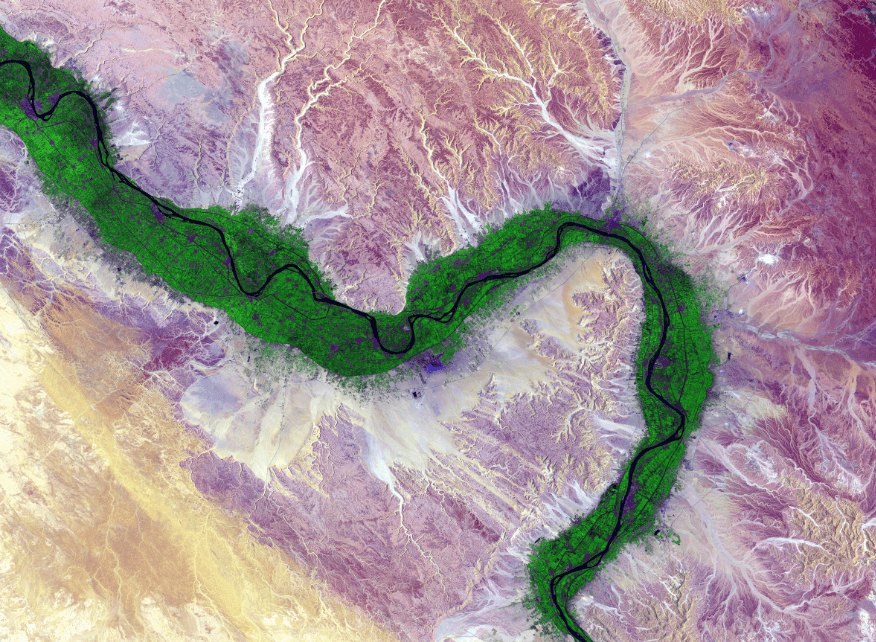

It is the next passage, though, that makes me think that we are definitely talking about Egypt here, because Yosira apparently taught the people all about cultivation and irrigation in a climate and area that was dictated by ‘the living waters that rise and fall like the chest of a breathing man’, beyond the reach of which waters ‘the land is dead’. Now that, to me, has ‘Nile Valley’ written all over it, what with its annual and predictable inundations (pre-Aswan Dam of course) and with the barren desert, beyond the influence of the life-giving waters, stretching away on either side. The scribe also makes the comment, here, that, even in those long distant times, men understood that it wasn’t just the water that gave life to the soil year after year, but the nutrients in the water that were carried along in it as sediment. The scribe also makes passing mention, at this point, that the god of The Kolbrin can be described as a ‘threefold’ god, thereby hinting at the concept of ‘aspects’ of a one god that we find in several global religions – both past and present – such as the Hindu pantheon and the father-son-spirit trinity of Christianity.

The narrative gets a little weird in the next passage as Yosira is said to have a peer-to-peer conversation with Panheta, the god of the Children of Panheta whom he had freed from the deceitful evil of the Charmers. Personally, I take that as Yosira doing what he did best and dovetailing his own philosophy with that of his ‘new’ people, so that his message was less of a shock to their existing thought processes, and he could work the new adherents into his system with minimum opposition. The aim, according to the scribe, was to build a common set of laws, whether its adherents dwelt in the cultivated areas or the desert. The collective term for the people of this common-law area seems to have been the Inta (this is the first time that word is used) and any man or woman who chose to live within its jurisdiction were obliged to abide by its laws and give up any former allegiance or customs. Yosira is beginning to build up quite the little state at this point, isn’t he!

The remainder of the chapter gets a bit hotch-potchy and reads like a random selection from the laws that Yosira set down for the Inta:

Man’s spirit follows the flow of the water so his body, when he dies, must be buried aligned along the ‘great river’ (i.e. The Nile).

Arable land and its produce are to be held in common. Each man and woman can take daily whatever herbs and fruit can be gathered in the hands and consumed before sunset. Only enough cereal crops may be gathered to keep one jar filled per person. The remainder must be placed in a communal repository but only after it has been heated and then cooled (sensibly sanitised and preserved in other words).

The spirit of life resides in all trees and plants (also in their fruit) so no edible-fruit bearing growth may be cut down (a very sensible precaution to keep supply going).

The spirit of life resides in all animals so slaying them for food is allowed but for no other reason. Once slain, the head and entrails must be buried and everything else eaten or burned except for the bones and skin which can be put to practical use (again, very practical guidelines for avoiding putrefaction and disease, and ensuring a regular food supply by forbidding unnecessary slaughter).

Be very careful with fire! Only generate it under controlled circumstances. Keep it bright and avoid creating too much smoke. Use only what wood you need and keep the blaze confined to prevent it spreading out of control (again, eminently practical advice from Yosira to avoid infernos and preserve supplies in an environment in which wood was probably not too abundant).

Every man and woman who ‘comes of age’ must take a mate. If they don’t they are not held in high regard by the rest of the community (I know, I know; it’s not very ‘modern’, but in a ‘primitive’ society maintaining and growing population numbers was a lot more important than it is now).

Crimes must be met with the punishment their severity deserves. Precedent can help with this (a practical building up of precedent, against which to judge new cases, can also be seen as a deterrent as citizens will think twice about doing something against the law if they know how they will be punished).

The chapter ends with Yosira hailing the Inta as his ‘unweaned children’.

Well, just a short chapter there, but an interesting one. It’s all about civilising and reining in the bestial excesses of man. On that level, the wonderfully practical Yosira/Osiris does a splendid job – you really do have to admire the way he ‘manipulates’ everybody into doing what he wants (which is always well-intentioned and, ultimately, for their own good) by employing the twin goads of supernatural scaremongering and actively demonstrating the practical benefits of toeing the line – I mean, who wouldn’t think the guy who showed them how to make beer was a top bloke?

From a self-help perspective, though, we can look at what Yosira offered his people on a, for us, altogether more personal (rather than societal) level. The reining in of destructive attitudes and behaviour is always going to reap longer term benefits, freeing us up to channel our spare energy into positive relationships and pursuits rather than negative and angry ones.

The parable-like story of the Charmers and the Kamawan can also be taken in that light. When we allow the darkness inside ourselves to ‘steal’ us away, we do become mute, in the sense that we cease to communicate to others what is really wrong, hindering any attempt on their part to help. And, just as the poor wretches in the story were in a continual state of torment because they couldn’t locate the splinters that had been inserted into their bodies, so we, in our inner despair, become restless and agitated, scratching around in vain for the increasingly elusive source of our own problems.

The Inta found their solution in the arrival of Yosira who saw the deceit, the false situation, for what it was, and took active and practical measures to prevent it from recurring. For us, then, in the insanity of this modern world, we have to interpret Yosira as active, outside, remedial energy. When we are down, when we are grieving, when we are angry, or hurt, or even just annoyed or bored – whenever, in fact, we find our way forward blocked – the most important thing is to stop and think and look around for a solution to remove that blockage. You may find the answer by employing your own Reason (with a capital R). You may find your answer in a walk, a run, a swim, in any form of exercise. You may find your answer in the beauty of the world around you, in the smile of a stranger, in a quiet word with a friend. You may find your answer in a book, a magazine, an internet website. But the important – the very important – thing, is to understand that there is an answer. All you have to do is recognise it. In many, many cases we come out the other side of the darkness, blinking in the new light, clear in the realisation that our problems, our blockages were, for the most part, just like the Kamawan, nothing more than deceit and illusion.

OK, that’s enough for today. The next chapter is entitled The Tribulations of Yosira and it’s the last The Kolbrin tells us about that incredibly fascinating character. I hope to see you there.